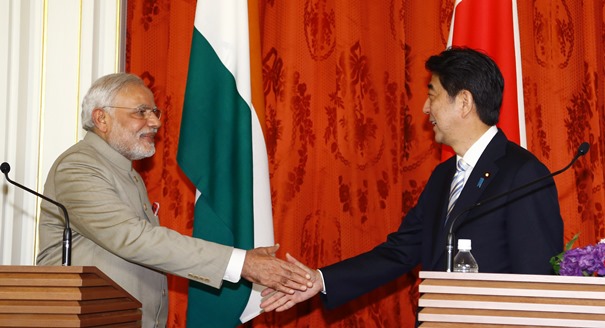

India’s newly-elected Prime Minister Narendra Modi visited Japan from August 31 to September 3 on his first trip to the country since taking office in May. During the visit, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced that Japan would increase its investment in India’s economy, pledging about 35 billion dollars of private and public money over the next five years. Pundits have wondered whether Japan and India are teaming up against China and speculated that Japan has replaced Russia with India as a counter balance to Chinese power.

Though such views have a kernel of truth to them, Japan’s pivot to India is not new: Japanese development aid to India (mostly long-term soft loans) amounts to about 30 billion dollars, and private FDI in 2013 alone totaled around 2 billion dollars. Japanese electronics and automobile factories have become an integral part of the Indian economy. Abe and Modi’s longtime friendship makes further integration highly likely.

However, India is not eager to be treated as a mere counterweight to China. Modi’s administration feels that India can manage China alone. The Indian Ocean, a vital sea route for China, is under firm control of the Indian and the U.S. navies. Instead of unnecessary confrontation with China, India is poised to exploit both China and the West for her own development. It will not be easy to replace China as the dominant economic power in Asia. India’s evolving democracy and confused property laws have hampered economic growth. Various political parties rule provinces with divergent ideologies and uncommon laws; farmers are unwilling to sell their land to the government to develop infrastructure. Modi maintained a restrained tone about China during his Japan trip. He did not give outright support to Japan’s proposal to hold a 2+2 format meeting (simultaneous meetings of foreign and defense ministers).

All this testifies to the fact that economic considerations trump political ones in East Asia. The countries in the region are economically dependent on each other, and no nation wants to isolate itself. True, China, partly out of hubris and partly out of domestic power struggles became too aggressive for a while, but now Xi Jinping is set to embark upon a goodwill diplomatic mission to the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation summit meeting in Beijing this autumn. He subdued criticism of Japan on the anniversary of China’s victory over Japan in 1945. The Chinese press has started to avoid excessive anti-Japanese sayings.

East Asia is coming back to a phase in which economic considerations dominate; if free trade is secured, almost all countries in East Asia are happy, and territorial disputes can be shelved.

In this milieu Russia may lose her place in East Asia, because it will be deprived of an opportunity to play China against the West. On the contrary, if Russia continues her vain efforts to realize economic integration around itself, it will be Russia that be played against China in Central Asia.

If Russia ever wants to return the glory of its past, why does it not refer to the “silver age”, when foreign capitals boosted her prosperity, the Morozovs and others, former serfs, built sound business, and poets and writers ushered in a golden age of the Russian culture—the template for a true soft power of Russia.