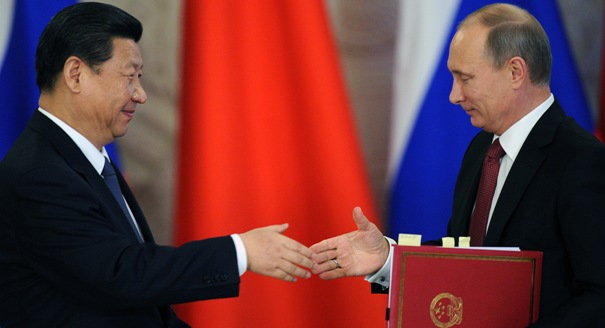

President Vladimir Putin is planning an official visit to China in late May. On its sidelines, he may attend the summit of CICA (Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia), to be held in Shanghai on May 20-21. Offshore of Shanghai, the Russian Navy will show off its muscle in a joint exercise with the Chinese (to defend the Chinese coastline?). For China, it will be a wonderful occasion to demonstrate that China and Russia are “in charge” of the security in eastern Eurasia. For Russia, it will be an opportune moment to show to the world that, despite Ukraine, Russia has a dear friend by the name of China, the second largest (purportedly the first in real purchasing power) economy in the world with a 1.4 billion population.

In East Asia, too, faire is foule, and foule is faire. Whether China versus the United States, China versus Japan or India versus China, although they are portrayed as staunch political and military rivals, they share large and close economic relations. Vietnam and the Philippines, which have now heated territorial disputes with China, also actively promote economic relations with China. This means that if Russia overly takes sides with China in political and security affairs, it will estrange, if not antagonize, major countries in East Asia and will drive Russia even closer to China.

Russia may think that Asian nations anyway need friendship with Russia for the latter’s oil and gas. But even if China monopolizes the Russian natural resources, Asians will not be terrified, because China’s need for oil and gas elsewhere will be eased, and the global oil and gas prices may fall. Even Japan, which allegedly thirsts for oil and gas because of the total closure of her nuclear power plants, will not grumble; her import of oil and natural gas has not increased in physical volume after the great earthquake in 2011, and the Japanese now spend less electricity.

Therefore, if Russia allies with China too closely, it will not only estrange Russia from most of Asian countries, but also may provoke China’s appetite to gobble the newly-born child of Russia, the Eurasian Union.

In the immediate wake of Putin’s China visit, a chain of important events will follow: the presidential election in Ukraine (it may well be postponed) on May 25 and the pompous inauguration of the “Eurasian Union” on May 29. This means that Russia’s behavior in coming few weeks will largely determine her position in East Asia for years. An intricate balancing act is needed for Russia.

Russia may be able to rightly gauge the importance of Japan. But it tends to underestimate the power which the ASEAN yields. The aggregate GDP of the ASEAN countries (2.1 trillion dollars in 2011) is on par with Russia, and the RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) under their auspices may become a basic framework for international trade in East Asia.

In East Asia today, along with the 19th-century-style imperialist confrontation, 21st-century-type economic integration is proceeding. How to deal with this region will be a good litmus test to measure Russia’s modernity.