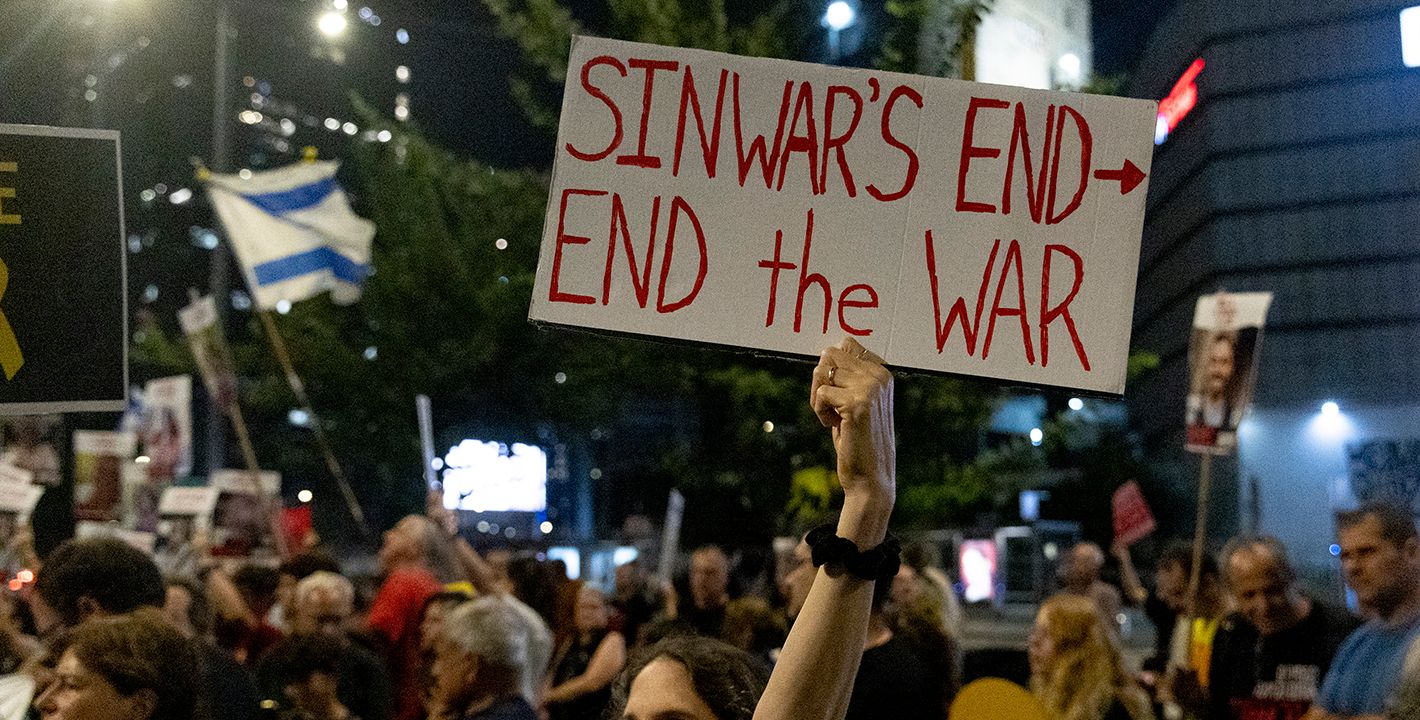

As observers reach their conclusions about the impact of the killing of Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, it is important to establish what has not changed. While U.S. President Joe Biden and others have noted that Sinwar’s elimination provides an “opportunity to seek peace” in Gaza, and move to the “day after,” no one should ignore—certainly not in Washington policy circles—the multitude of elephants in the room still prevailing in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

The fundamentals in this conflict are tied to sovereignty and occupation, as well as peace and war. On the first, the United States has recognized time and again the need to “set the conditions for a better future, including a two-state solution”—in other words, ending the Israeli occupation and establishing Palestinian sovereignty. There is a temptation to reduce the discussion today to Hamas and the fate of its leaders, but Israel’s occupation of Gaza, East Jerusalem, the West Bank, and the Golan Heights predates Hamas’s existence by two decades. As for peace and war, though Sinwar organized the attack of October 7, 2023, he was not the principal target of Israeli strikes on Gaza after that date, nor was he the main obstacle to negotiations in the past year. Had he been, Israel’s position today would be very different.

Israel has been quite transparent about all of this. Israeli media outlets have reported multiple times that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was actively “foiling talks” designed to secure the release of Israeli hostages from Hamas captivity, and to provide for temporary pauses in the fighting—pauses the Biden administration claimed it hoped would lead to a permanent ceasefire. Moreover, despite the administration’s characterization of these as being ceasefire talks, Netanyahu’s government clarified that Israel had no intention of stopping the war until “total victory.” One can support or oppose these positions on war and peace, but they are very clearly Israeli positions, expressed by Israeli figures.

Israeli views on occupation and sovereignty have also been transparently laid out. In August, the Israeli Defense Ministry’s Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories created a new position for Gaza that parallels that of the head of the Civil Administration in the West Bank. It establishes an Israeli military overseer of civilian affairs in Gaza. Nor is this a short-term endeavor. As one Israeli news site reported, “‘[T]his position will be with us for years to come,’ a senior [Israeli] defense official [stated], dismissing the notion that Israel’s involvement in Gaza will end soon, regardless of the pace of the fighting or any potential hostage deals.”

Unpalatable as it may be in some quarters, the Israelis have made it amply clear they are not leaving Gaza. On the contrary, senior ministers, such as National Security Minister Itamar Ben-Gvir, recently repeated his call for Palestinians to be the ones who leave Gaza. On multiple occasions, most recently this week, Finance Minister Bezalel Smotrich has also called for permanently resettling Gaza. Talk of a “day after” for the territory in the short term is thus unrealistic. Indeed, it may be that a “no day after” scenario is precisely the point. A “forever war” would be implemented by design, for reasons with which external actors might disagree, but for which the Israelis have nonetheless established, quite openly, their rationale.

Looking at East Jerusalem and the West Bank, there is no suggestion Israel is considering a withdrawal from there either. In July, Israel announced the largest expropriation of land in the West Bank since the Oslo Accords were signed more than 30 years ago. Smotrich explicitly declared that such a move was aimed at “thwarting the danger of a Palestinian state,” and he did not mention Hamas. Despite the fact that the International Court of Justice ruled in July that, “Israel is under an obligation to bring to an end its unlawful presence in the Occupied Palestinian Territory as rapidly as possible,” there is no sign that Israel will change its policies in that regard. On the contrary, it is solidifying its position.

None of these issues, tied to sovereignty and occupation or peace and war, were impacted by Sinwar’s killing. Fundamentally, those issues were shaped by Israeli decisions, not Palestinian ones, whether they involved Hamas or otherwise.

But there is a major factor in the Israeli calculus that is particularly pertinent for the Washington policy community. It is the Israeli assumption that the United States will back Israel irrespective of any dissatisfaction with Netanyahu and his government. Such an assumption is well-placed. During the past year, the Biden administration has set multiple “red lines” for Israel in its prosecution of the Gaza war. In response, Israel opted to proceed anyway. The most recent example was U.S. insistence that Israel call off the mass evacuation of northern Gaza and boost humanitarian aid into the territory, where nearly 90 percent of humanitarian supply efforts have been impeded. American law stipulates the suspension of military arms transfers in cases where a recipient is not complying with international humanitarian law. Yet despite the dearth of humanitarian aid allowed into Gaza, U.S. support for Israel has remained intact.

Israel has made it clear that Sinwar’s death does not represent much of an opportunity to end the Gaza war. The Biden administration does not need to wait for an opening to stop the conflict; it can create one itself. The United States has the power to end the violence, and to ensure a peaceful resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. It simply needs to use that power. Continuing to avoid such outcomes, and redirecting attention away from the core factors underpinning this conflict, will only ensure instability and insecurity for many years to come.