Fifty years ago, on October 6, 1973, Egypt and Syria launched a daring attack against Israel on two fronts, seeking to reclaim territories lost during the Arab-Israeli war of June 1967. This was a pivotal moment in the history of the modern Middle East as Israel was caught off guard.

The attack took place on Yom Kippur in Israel, on the tenth day of Ramadan in Egypt and Syria, and pushed the world to the brink of a nuclear confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union. After it became clear that Moscow was resupplying the Arab states with weapons, then president Richard Nixon dispatched massive weapons shipments to bolster Israel’s defenses. After more than two weeks, the Israelis managed to move to within striking distance of Cairo and Damascus, securing a substantial military victory.

Despite this, a deep-seated uneasiness festered in Israel, which had hitherto regarded itself as militarily invincible. Simultaneously, a renewed sense of dignity was perceptible in Egypt, playing a role in Egyptian president Anwar Sadat’s decision to sign a peace treaty with Israel in 1979. But the repercussions of the 1973 war extended far beyond the immediate conflict, leaving a lasting impact on the region, including Lebanon, which had a front-row seat to what was going on.

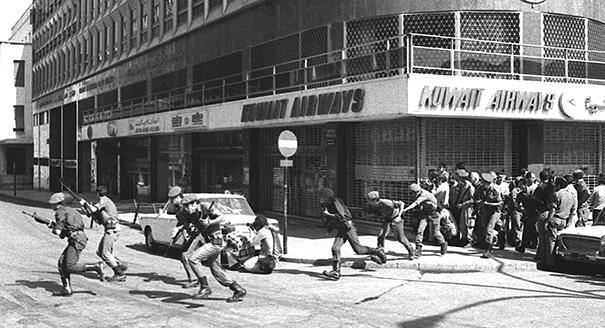

During the war, Lebanon was both witness to the conflict’s impact and was experiencing its own set of challenges. The year 1973 had started off eventfully for the country. In May, the Lebanese armed forces launched an offensive against Palestinian guerrillas, employing jet aircraft and tanks, resulting in a two-day confrontation. The root cause of this clash lay in Lebanon’s distinctive situation as the headquarters of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), while hosting tens of thousands of disenfranchised Palestinian refugees. Lebanon had signed the Cairo Agreement of 1969, which allowed the PLO to arm and govern itself within the refugee camps, establishing a de facto state within the Lebanese borders. While Lebanon did not participate in the 1973 war, it was entangled in the regional dynamics that the war brought to the forefront. This was partly due to the fact that the country’s southern and eastern regions had been transformed into corridors by Israel’s air force to raid Damascus and other cities in Syria.

On the war’s first day, the Arabic-language daily Al-Nahar reported that Lebanon’s president, Suleiman Franjieh, expressed his support to Syrian president Hafez al-Assad. A day later, the PLO leader Yasser Arafat, who was based in Lebanon, told Sadat and Assad that Palestinian forces controlled the western side of Mount Hermon. The early days of the war seemed surreal to the Lebanese. On October 8, Al-Nahar ran a story stating that many residents of Beirut didn’t believe a war was happening. However, this perception gradually shifted as Palestinians in the refugee camps went on high alert, and Syrian and Israeli aircraft began crashing into southern towns, from where people could watch aerial dogfights in the skies above.

While the state wasn’t directly involved in the conflict, many of its citizens were deeply engaged in it. On the third day, the Lebanese Press Syndicate called for the “unification of Arab media efforts” in the war, and a communique issued by “intellectuals and journalists” expressed their backing for the Arab forces. The PLO and other leftist groups organized demonstrations in solidarity with Cairo and Damascus, while American University of Beirut students went on strike in support of the struggle and administered first aid lessons on October 11. There were blood donation drives across the country, and medical teams from the American University Hospital went to Syrian hospitals to provide aid. Meanwhile, warplanes continued to crash in Lebanese territory, while an unidentified object fell off the Beirut coast, which the army investigated on October 13.

The government rationed fuel because of the war and introduced a traffic regulation system, so that those with even and odd license plate numbers could only circulate on alternative days (a practice that would be echoed nearly 50 years later during the COVID-19 outbreak). Complaints abounded regarding the perceived unfairness and constitutionality of the measure. The war halted a heated parliamentary debate over reforms to Lebanon’s municipal laws and the holding of municipal elections. It wasn’t until 1977 that parliament passed the legislation, and municipal elections wouldn’t resume until 1998!

However, the most remarkable incident during the war involved a bank heist. On October 18, a small left‐wing guerrilla group called the Revolutionary Socialist Organization seized control of the local branch of Bank of America, taking several people hostage and making audacious demands, including the release of jailed Palestinian guerillas held in Lebanon, a $10 million ransom to help finance the war effort, and safe passage to Algeria. The following day, police raided the bank after the kidnappers executed a hostage—an American bank employee. The operation ended with four fatalities, including a police officer and the group’s leader. The episode foreshadowed the violent times that lay ahead for Lebanon.

The country’s internal divisions persisted during this tumultuous period. In the south, residents fled their towns due to the perilous security situation, leading southern lawmakers to condemn the government’s handling of the situation. Border towns bore the brunt of the conflict as battles raged between Israelis, Syrians, and Palestinian guerrillas, resulting in numerous attacks and infiltration attempts by the PLO. Meanwhile, amid the chaos, the Lebanese football federation still had time to declare Nejmeh Football Club winners of the 1972–1973 championship, marking its first-ever victory. This announcement came just two days after the passage of Security Council Resolution 338, which called for an immediate and comprehensive ceasefire by all parties in the war.

However, Lebanon did not participate in any post-ceasefire negotiations with Israel, despite some encouragement by lawmakers, such as Raymond Eddeh, to do so (in order to guarantee security on Lebanon’s southern borders). The 1973 war also reinforced the relationship between the Lebanese and Syrian presidents. In January 1974, Franjieh and Assad held a summit meeting—a significant event as it marked the first visit by a Syrian head of state to Lebanon in eighteen years. All the while, Beirut was gradually losing control over its borders and its ability domestically to dictate matters of war and peace.

A year and a half after the October war, Lebanon would descend into civil war in April 1975. Subsequently, in 1976, the Syrian army would enter Lebanon, under the pretext of preventing a PLO victory, which would very likely have led to a new confrontation between Syria and Israel. In 1978, and again in 1982, Israeli forces would also invade Lebanon. Lebanon, which had stood on the sidelines of the Arab-Israeli wars, would very soon become the centerpiece of Arab-Israeli hostilities.

Despite the eventual withdrawal of the Israeli and Syrian armies in the first decade of the new century, Lebanon has yet to fully recover from the tumultuous events of the 1970s, including the October 1973 war. The early 1970s began to magnify the challenges the country faced in a violent neighborhood. As the October 1973 war raged, Lebanon held a unique position in the midst of the region’s turmoil. Yet many Lebanese often chose to ignore what was going on, despite the echoes of fighter jets and the sights of falling aircraft. This attitude would soon change.

One could argue that Lebanon’s civil war began much earlier than 1975. The war of 1973 was both a reminder of the country’s ability to skirt the disasters taking place all around it, but also a forewarning that sooner or later what happens in the Middle East usually finds its way to Lebanon’s doorstep. Five decades later, the echoes of the 1973 war continue to resonate in the country and across the region.