Sarah Yerkes | Senior fellow in the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

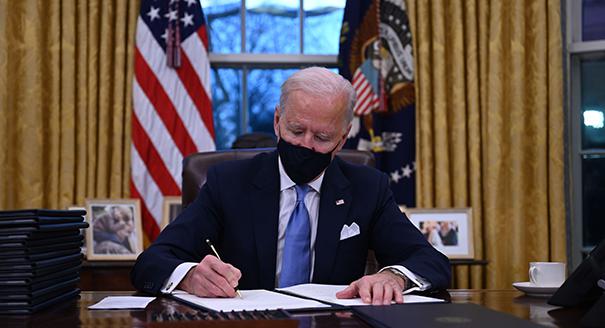

For those who expected an abrupt break from the Trump era, the Biden administration’s approach to the Middle East and North Africa thus far has been disappointing. While President Joe Biden has repeatedly pledged to defend democracy and human rights around the world, in the Middle East in particular he has not delivered on that pledge.

The administration has taken some very small steps toward reintroducing values into the U.S. approach toward the region, but too often these measures have been outweighed by larger signals and policies that make clear that much of the administration’s commitment to democracy and human rights is little more than empty rhetoric.

In Saudi Arabia, while Biden has refused to engage personally with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, he has also failed to hold him accountable for Jamal Khashoggi’s murder, despite U.S. intelligence confirming the Saudi royal’s complicity.

The administration’s decision to freeze $130 million of Egypt’s $1.3 billion aid package neither satisfied Egyptian and American human rights activists nor signaled to President Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi that the “blank checks” were over.

The Biden administration’s approach to Tunisia’s democratic backsliding has also been ineffective. Despite repeated high-level engagement with President Qaïs Saied following his July 25, 2021, coup, and numerous public and private statements calling for a return to the democratic path, Saied’s consolidation of power has marched forward unabated. The State Department’s most recent statement welcoming Saied’s unconstitutional, nontransparent, and exclusionary road map only serves to undercut the narrative that democracy is a top U.S. priority in Tunisia.

Aaron David Miller | Senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, where he focuses on U.S. foreign policy

Franklin Delano Roosevelt reportedly quipped about Abraham Lincoln— undeniably America’s greatest president—that he died a sad man because he couldn’t have everything. Governing is about choosing, and it seems, at least a year into his administration, that President Joe Biden has made a choice, namely that the Middle East isn’t at the top of his priority list. In a recent interview, National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan failed to even make mention of the region.

America isn’t withdrawing from the region. There is no shortage of envoys and visitors from Washington. Humanitarian assistance, deployments of military assets, and commitments continue to be quite robust, especially in the Gulf. And the talking points—support for a two-state solution for the Palestinian-Israeli conflict; a political settlement in Syria; and an end to conflicts in Libya and Yemen—all sound good. But the bandwidth for actually investing resources and leadership in any of these rather hopeless enterprises just isn’t there.

Other priorities abound, among them America’s own broken house, a rising China, Vladimir Putin and Ukraine, and a feeling that seems to pervade the upper reaches of the Biden administration that the Middle East is a region where American ideas and resources go to die.

The one issue that the administration seems to care most about is constraining Iran’s nuclear program through negotiations. A regional conflict involving Israel and Iran that might possibly draw America back in would be bad for domestic recovery, triggering rising oil prices and falling markets. But even here, the toxic politics surrounding the Iran issue in Washington and the new hardline Raisi government in Tehran have made the U.S. approach to the Vienna negotiations cautious and risk-averse.

Will any of this change in 2022? When asked what could alter British policy, prime minister Harold Macmillan quipped, “Events, dear boy.” With midterm elections looming, the propensity of the Biden administration will be to avoid issues involving political risks. But as the May 2021 conflict between Israel and Hamas showed, and with the real possibility of tensions between Israel and Iran, Biden may want to be done with the region. But the region may not be done with him.

Yasmine Farouk | Nonresident scholar in the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment of International Peace

“There is a fundamental proposition, this partnership with Saudi Arabia is an important one.” The statement by U.S. Secretary of State Anthony Blinken sums up the Biden administration’s policy of “recalibrating” relations with Saudi Arabia after one year in office. The administration started its mandate with an emphasis on values in foreign policy in general, and with Saudi Arabia in particular. However, its first year in office almost ended with the assertion that the United States is “going back to basics” in its relationship with its partners in the region. Values were never among the basics of the relationship with Saudi Arabia.

Although President Joe Biden has significantly downgraded and shaken up the relationship with Riyadh, his administration has had to face the reality that Washington needs to turn down the heat on Saudi Arabia since it still needs the kingdom’s cooperation in the Middle East and beyond.

Countering Chinese influence, stabilizing oil prices to “build back better,” proving that democracy can deliver, reaching a deal with Iran, and maintaining congressional support, for instance, by resolving the conflict in Yemen all necessitate cordial relations with the Saudi leadership.

Riyadh has also learned that other Gulf countries make Saudi Arabia no longer as indispensable as it was for the United States, and that it needs to make concessions in order to maintain U.S. support at a time when it badly needs it. Saudi Arabia has released some political prisoners, dialed back its hawkish foreign policy, and even launched two green initiatives, keeping up with Biden’s focus on climate change. Meanwhile, it has also pursued its policy to diversify its international relations and signaled that it won’t toe Washington’s policy line on oil, China, or even Yemen.

The two sides are trying to meet each other halfway, which is in both countries’ interests. But when he was a candidate, Biden had promised to go all the way in taming Saudi Arabia. Now we can see this won’t happen.

Karim Sadjadpour | Senior fellow in the Middle East Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

The Biden administration’s stated objectives for their Iran policy was to revive the 2015 nuclear agreement with Tehran, and follow it up with a “longer and stronger” agreement that would address the agreement’s expiring provisions as well as Iran’s missile program and regional policies.

Despite nearly a year of intermittent negotiations in Vienna, senior Biden administration officials are privately pessimistic that Iran will be willing to reverse it nuclear program to where it was in 2015, and doubly pessimistic about the possibility of achieving a “longer and stronger” agreement. What appears likelier, at least at the moment, is a potential interim agreement in which Iran would agree to limited nuclear compromises in exchange for limited sanctions relief.

Despite the Biden administration’s attempts to deescalate with Iran, Tehran’s longtime policies and its regional alliances and partnerships have continued unabated. Over the last year Lebanese Hezbollah has continued to assassinate its critics, Iraqi Shia militias have launched an assassination attempt against Prime Minister Mustapha al-Kadhimi, and Yemen’s Houthis have launched repeated missile and drone attacks against civilian outposts in the United Arab Emirates.

In contrast to 2015, when the Obama administration hoped that a nuclear deal could potentially transform the U.S.-Iran relationship and Iran’s domestic reality, this time around there is a much more sober understanding that a nuclear agreement is unlikely to lead to a U.S.-Iran breakthrough or moderate Iran’s internal or regional policies.

Maha Yahya | Director of the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut

The Biden administration has focused on tactical measures that have been inconsistent with achieving its primary goal of stability. Attempting to balance values with strategic interests has led to a transactional approach where each overriding priority—nuclear negotiations with Iran, combatting terrorism that may threaten the U.S. homeland, protecting international trade and waterways, and supporting a broader integration and deescalation policy in the Middle East—is being addressed independently of other objectives. The actions taken to achieve each of these have created dynamics that often undermine Washington’s stated goals. The reason for this is that the regional challenges that Washington is facing are highly interconnected, but the policies are not necessarily so. Consequently, actions meant to address one particular issue may result in a considerable and contradictory impact on other issues.

For example, a nuclear deal that would contain Iran’s nuclear options is in itself a worthy objective, but on its own would likely spur more regional instability. That’s because the sanctions relief that would follow is likely to translate into additional funding for Iran’s proxies across the region, which in time would provoke state failure in some places, and undermine trade and hopes of deescalating tensions elsewhere.

Similarly, the creation of a stable regional environment as the United States disengages militarily from the Middle East is also fraught with contradictions. As the post-Cold War order imposed by Pax Americana has dissipated, regional states have developed a more expansive interpretation of their national security and have become much more proactive about shaping military and political outcomes in Arab countries, some of them far away. The behavior of Turkey and the United Arab Emirates are prime examples. This process has led to a much more fragmented, less cohesive region, one in which stability remains elusive.

Meanwhile, normalization efforts by Arab allies of the United States with the Assad regime in Syria is undermining demands for accountability and justice, as well as U.S. efforts to use economic pressure to force Damascus to make political compromises. Without the prospect of justice for the crimes they committed, including crimes against humanity, regimes throughout the region will have no incentive to refrain from abusing their own populations, which is inherently destabilizing. By the same token, looking at terrorism in isolation of the broader political and socioeconomic environment of countries in the region is meaningless if it fails to lead to long-term solutions. This includes addressing feelings of political exclusion, socioeconomic injustice, and widespread corruption.

Failing to examine the interconnection of policy goals, actions, and repercussions will only lead to greater volatility that will have impacts far and wide. In time, this will only pull the United States back into a region that Americans feel has absorbed too much of their energy.