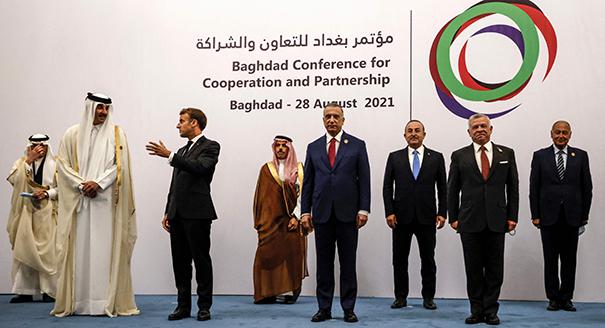

On August 28, Baghdad hosted a unique gathering of heads of state and representatives of countries neighboring Iraq (except Syria). This included the leaders of France, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, and Qatar. The gathering, which was labeled the Baghdad Summit for Cooperation and Partnership, was meant to show support for Iraq as it faces political, security, and economic challenges, while it also recognized the efforts of Prime Minister Mustapha al-Kadhimi’s government in promoting regional dialogue.

For Kadhimi, the summit achieved three goals. First, it was a culmination of his efforts to reposition Iraq at the intersection of regional relations—or as Kadhimi likes to put it, as a bridge between countries of the region. Since he was director of the Iraqi National Intelligence Service, Kadhimi has developed an extensive network of relations with Middle Eastern leaders and senior officials, achieving much success in playing the role of honest broker and dialogue facilitator, especially between Iran and its regional rivals. A “zero enemies” approach has guided his handling of regional ties.

Kadhimi is not Iraq’s first prime minister who has advocated nonalignment with any of the regional axes. However, his reputation as someone who is moderate, pragmatic, and nonsectarian, and who is less swayed by Iran than his predecessors, has earned him more credibility. At the same time, his regional policy has been established on hard realities. Iraq today is a fragile state situated between three regional rivals—Iran, Turkey, and Saudi Arabia. Kadhimi thinks that by proactively seeking to minimize differences between these powers, Iraq could create a more positive regional role for itself than simply representing a battlefield for its neighbors.

Previously, the United States was essential in establishing contacts between Shia-led Iraq and Washington’s regional allies. Now, as the Americans have become more disengaged from Iraq, and arguably from the Middle East altogether, France and other countries, among them rising regional powers such as Iran and Turkey, have tried to fill the vacuum. In this tangled situation, the Iraqi government has sought to maneuver among these external actors in order to enhance its margin of action. This approach has been helped by Iraq’s oil wealth, which provides economic independence, but is hampered by deep domestic divisions, powerful paramilitary groups that have their own foreign policy, and corrupt and dysfunctional state institutions.

The summit was a manifestation of reduced U.S. involvement and the need for a new institutional skeleton that reflects emerging power relations in the region in which both Iran and Turkey have seats at the table. It could also be the beginning of a search for a new conceptual framework regionally that overcomes previous dichotomies that were defined in sectarian (Sunni vs. Shia), ideological (Islamists vs. Secularists), or geostrategic (pro-West vs. anti-West) terms.

This leads to Kadhimi’s second objective, namely containing Iran. Given Iran’s sway in Iraq through its network of local allies and paramilitaries, which is unmatched by any other regional power, Kadhimi is looking for ways to check this influence without provoking Tehran’s hostility. Such hostility would not only destabilize his government, it might terminate any hopes he might have to stay in office after Iraq’s next parliamentary elections on October 10.

Kadhimi is also trying to prove to the Iranians that his approach, rather than that of their ideological and sectarian allies, would bring real gains for Tehran and break its isolation. This is especially true considering that Ebrahim Raisi’s government has declared that its foreign policy would prioritize improving Iran’s relations with the region. Indeed, Kadhimi has already succeeded in hosting talks in Baghdad between Iran and Saudi Arabia to discuss the two countries’ disputes. By accepting a leadership in Baghdad that is not ideologically allied with its “revolutionary” anti-American approach, Iran could potentially secure a functioning channel to the Arab world and obtain regional recognition of its role and interests.

This is tied in to Kadhimi’s third goal, namely enhancing his chances of remaining in office after the election. Kadhimi is not running in the election and is positioning himself as a neutral actor whose main interest is to guarantee free and fair voting. But this is also a strategy to maintain his chances of being a compromise candidate for the post of prime minister who reflects a minimal consensus among competing parties and centers of power. Absent a significant internal achievement that could brand him politically and render him irreplaceable, Kadhimi seeks to draw attention to his foreign policy successes. In a system where elections alone do not determine who is going to lead the government, gaining more international legitimacy could favor one candidate over another. Indeed, this is truer in Iraq, where the common wisdom since 2005 is that nobody can be prime minister if the United States or Iran oppose his nomination.

Despite their expressed disapproval of Kadhimi, most Iran-allied factions will have to consider, if not assent to, whatever Iran decides. It is hard to predict what that position could be and how it might be shaped in the absence of Qassem Suleimani, the late head of the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, who was heavily involved in the formation of Iraqi governments after 2005. But under any circumstances, the nomination of Iraq’s next prime minister will surely be influenced by the regional context and balance of power.

As the Baghdad summit showed, Mustapha al-Kadhimi aspires to reshape this balance by safely distancing his government’s agenda from Tehran’s, while also facilitating Iran’s increasing integration into the emerging regional order.