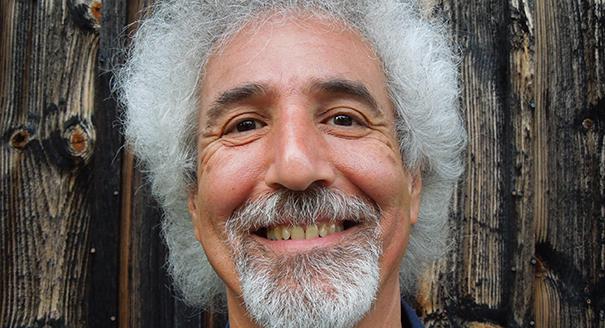

Interlink Publishing is a Massachusetts-based independent press that publishes approximately 50 books a year. Although its titles range from cookbooks to children’s literature, Interlink is arguably best-known for publishing English translations of major works of fiction from the Arab world and Africa, and for nonfiction on modern Middle Eastern history. Michel Moushabeck is Interlink’s founder and director. A Palestinian born and raised in Lebanon, he has long made his home in the United States, where in addition to his Interlink-related responsibilities, he serves as percussionist for the Boston-based Layaali Arabic Music Ensemble and lectures widely on Arabic music. Rayyan Al-Shawaf interviewed Moushabeck by email in late May. Full disclosure: Interlink published Al-Shawaf’s novel When All Else Fails (2019).

Rayyan Al-Shawaf: What was your goal in establishing Interlink back in 1987?

Michel Moushabeck: When I set foot in the United States and experienced firsthand the bias in mainstream media reporting and Americans’ one-sided view, which was not accepting of Palestinian history and narrative, I became determined to do something about it. After graduation, I changed the course of my life and decided to start a publishing house without knowing anything about how books are edited, designed, distributed, publicized, or sold. I was twenty-something with a BIG idea: to bring the world closer to American readers and bring people of the world closer to each other through literature.

RA: Since you founded Interlink, the independent publishing house has introduced American readers to a host of Arab and African novelists and short story writers, many of whose works were not previously available in English. These have included Palestinian writers. As I’m sure Palestine is very much on your mind these days, tell us which Interlink titles by Palestinian authors would make for a good read, and why.

MM: My family is from Jerusalem and my parents suffered multiple exiles and displacements in their lifetime, so Palestine is always on my mind. At Interlink, my goal was—and still is—to commission, publish, and promote books that foster a better understanding and appreciation of other cultures. And, of course, Palestine and Palestinian literature figure prominently in my life and are integral parts of my mission. To genuinely understand Palestine, one must read Palestinian literature—the unofficial language of the people and the doorway to its soul. The Palestinian literary landscape is as rich and colorful as the Palestinian village embroideries old women wear proudly on their chests. Fiction classics such as Emile Habiby’s The Secret Life of Saeed: The Pessoptimist, Sahar Khalifeh’s Wild Thorns, Ibrahim Nasrallah’s Prairies of Fever, and Ghassan Kanafani’s All That’s Left to You remain all-time favorites of mine.

When it comes to more recent fiction and nonfiction in translation, I have several recommendations. Adania Shibli’s Touch, translated by Paula Haydar, which Publishers Weekly described as “exquisite” and “powerful,” takes place in the West Bank, where a young girl’s life is colored by tragic personal and political events. There is so much richness and beauty in this work. It has soul; it has rhythm; and it merits repeated readings. When you’re done reading Touch, I would highly recommend reading Shibli’s second novel, We Are All Equally Far from Love, translated by Paul Starkey.

Sonia Nimr’s debut novel, Wondrous Journeys in Strange Lands, kept me up all night when I first read it in Arabic. Thanks to a beautiful translation by Marcia Lynx Qualey, one can now read it in English. The story relates the adventures of Qamar, a young Palestinian woman who sets out on a daring journey to discover the world—on caravans and ships, and across empires. This richly imagined historical fable, which received much acclaim, recalls the famous travel narratives of the 14th century Moroccan traveler Ibn Battuta.

Palestine as Metaphor is the first English publication of a collection of interviews with the late Mahmoud Darwish, the beloved Palestinian poet and thinker. These interviews—elegantly translated by Amira El-Zein and Carolyn Forché—feature Darwish reflecting on his art, engaging in personal revelations, and offering political insight. Conducted by several writers and journalists, the interviews unravel the threads of a rich life haunted by the loss of Palestine, and illuminate the genius as well as the distress of a major world poet.

Finally, there is Wasif Jawhariyyeh’s memoirs, which won the Palestine Book Award. The Storyteller of Jerusalem: The Life and Times of Wasif Jawhariyyeh, 1904–1948 is a treasure trove of remarkable writings on the life, culture, music, and history of Jerusalem over a period of some four decades. Jawhariyyeh—oud player, music lover and ethnographer, poet, collector, partygoer, satirist, civil servant, local historian, devoted son, husband, father, and person of faith—viewed the life of his city through multiple roles and lenses. The entries in this book—which reads like a novel—were taken from a ten-volume, leather-bound diary that Wasif left us, parts of which have now been translated into English by Nada Elzeer, and edited by Salim Tamari and Issam Nassar. The result is a vibrant, unpredictable, sprawling collection of anecdotes, observations, and yearnings as varied as the city itself.

RA: During Israel’s past bombardments of Gaza, much of the world seemed to believe that once the Israelis ended their military campaign, we could all go back to ignoring the Palestinians and their demands. Do you think things will turn out differently this time?

MM: You’re right. News headlines will change tomorrow, but the violent assault on Palestinians’ lives and their rights to freedom and equality will continue. Occupation, oppression, and dehumanization are part of Palestinians’ daily existence. Remember, Israel bombed Gaza in 2006, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2014, 2018, 2019, and now in 2021. While the ceasefire may have temporarily halted the latest bombardment, displacement continues in Jerusalem alongside an Israeli police operation called Operation Law and Order in which 1,700 Palestinians citizens of Israel, including children, were arrested.

Yet the discourse has changed. In its latest report, Human Rights Watch demonstrates how and where Israel engages in apartheid. Hagai El-Ad, director of B’Tselem, one of Israel’s oldest human rights organizations, recently said: “Israel is not a democracy that has a temporary occupation attached to it: it is one regime between the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea, and we must look at the full picture and see it for what it is: apartheid.”

More and more of the mainstream media is now acknowledging what we’ve known for so long—that a whole new generation of activists views Palestinian rights and U.S. support for Israel through the lens of racial justice and stopping state violence. Young American Jews in particular are at the forefront of this movement. They have grown confident and unafraid of stating that Zionism is wrong and that Israel practices apartheid. And on May 28, the front page of the New York Times featured photos of the 69 children killed in the recent conflict. All but two were in Gaza. This is unprecedented from a mainstream newspaper that, in the past, consistently supported Israeli and Zionist views and actions. It’s our movement moment. And continuing to push is extremely important. Israeli apartheid continues, and so will our resistance.

RA: Among the Palestinians expelled by Zionist militias from Jerusalem’s Qatamon neighborhood during the Nakba were your parents, who wound up in Lebanon. You were born in Beirut in 1955 and lived there until 1975, when you left due to the civil war. Have you maintained a link to Lebanon in the decades since? What are your views regarding the current situation there?

MM: As you can imagine, Lebanon is also close to my heart. It is part of my DNA. I was born in Beirut and spent my formative years there until the age of 20 when the civil war broke out and turned our lives upside down. Over the years, I have published a large number of works by Lebanese writers, young and old, many of whom have become close friends. Currently, I am working on The Book of Queens, a novel by Joumana Haddad, and Memoirs of a Militant: My Years in the Khiam Women’s Prison, a memoir by Nawal Baidoun.

I am in constant touch with friends, writers, agents, publishing colleagues, booksellers, and educators in Lebanon. I can’t begin to fathom the hardships they are going through. There was a time when Lebanon was our most important market in the Arab world. Sadly, the economic collapse has made it difficult for people to spend money on books. The situation there is desperate at the moment. The August 2020 explosion that devastated Beirut has pushed people to a breaking point. It is heartbreaking to hear and read about the suffering of the Lebanese people, which has largely been brought about by the massive government corruption that has plagued Lebanon since its independence in 1943.

Of course, sectarian tensions and the interventions of outside forces have compounded the problem and played a major role in what is happening. However, I am hopeful and in awe of the fearless younger generation. These are the men and women who will one day turn things around and enable Lebanon to regain its position at the center of the Arab world’s cultural life. This is something I am certain of.