In Libya, Egypt is in a sort of debtor’s prison. Given the trajectory of the Middle East and North Africa since the so-called Arab Spring a decade ago, not to mention the 1,158 kilometer border shared with Libya and arms flows from the country to Sinai, Egypt’s involvement in Libya was virtually a foregone conclusion.

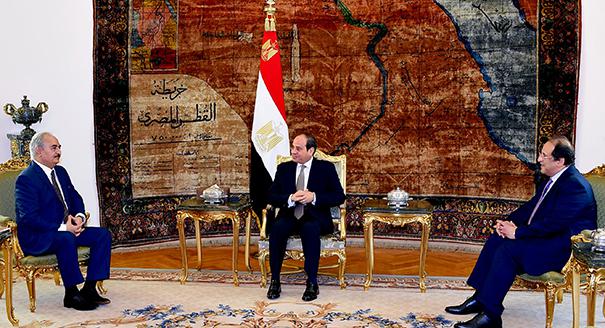

Egyptian intervention began in 2014 as rhetorical backing for a Libyan general perceived as being anti-Islamist, Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar, in a localized civil war. It quickly ballooned into the transshipment of arms, mercenaries, intelligence, and military advisers in an internationalized conflict involving a bevy of other countries. The stakes are high in Libya, but Egypt is committed. The debts it has incurred—political, financial, and ideological—will shape Egypt’s involvement and suggest that it may be in Libya longer than its interests would dictate.

The clearest debt is political. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) supported the Egyptian military’s coup against the former president Mohammed Morsi of the Muslim Brotherhood in 2013. In return, President ‘Abdel-Fattah al-Sisi committed, explicitly or implicitly, to backing these states’ counterrevolutionary reaction to the Arab Spring. Now Egypt is part of a proto-alliance of Arab states whose vision for stability and security in the Middle East relies on politics devoid of genuine dissent.

The effects of this proto-alliance are being felt in the swirling chaos of Libya today, where Haftar’s Emirati-, Russian-, and Egyptian-backed forces face off against militias backed by Turkey, which has bolstered the Tripoli-based Government of National Accord (GNA). Even though Egypt has tried to mediate between Haftar and the GNA, and even though not all elements of the Egyptian government agree with Haftar’s methods and aims, Turkey’s recent commitment to support the beleaguered GNA prompted Egypt to back Haftar, given Ankara’s strong backing for the Muslim Brotherhood.

This support may also be influenced by the position of the UAE, which has also firmly supported Haftar. Egypt has used its airspace, airlift capability, and bases in the Western Desert to support Haftar’s logistics train, even reinforcing his forces with mercenaries from abroad, not to mention providing intelligence and military advisors. After investing so much in this proto-alliance, to simply pull out now would be anathema. What is more concerning is that Egyptian leaders may not yet realize what cost in men and material their country may pay if a competing proto-alliance hardens and regional war ensues—with Libya only one of many potential battlegrounds.

In addition to these political debts, Egypt has financial interests and commitments that have kept it embedded in the Libya conflict. In the years since Sisi came to power, the value of the Egyptian pound has tumbled and a burgeoning military economy as well as outright political repression have prevented the development of the private sector and the rise of a confident, engaged Egyptian middle class. The billions of dollars flowing from the Gulf have not been enough to transform the Egyptian economy, and the chaos in Libya has choked off the remittances that Egyptians who worked there once sent back. If Egypt pulls out of Libya now, it would also lose the boon of reconstruction contracts there, which it can ill afford.

Egypt’s deepest debts are ideological, owed to its own people. Its alignment with the UAE and Saudi Arabia is no mere marriage of convenience, but a syndicate where the harshest treatment is reserved for any word or deed that smacks of political Islam, and even some that do not. The killing of seven Coptic Christians in February 2014 at the hands of Islamist extremists in Libya galvanized Egyptian support for involvement and created an obvious link to the Islamist insurgency in Sinai, which has received weapons and men from groups in Libya. These trends, combined with the anti-Islamist motivations of the UAE and the decisive repudiation of Morsi’s Islamist government, have cast an illiberal secular pall over the Libya war. To members of the proto-alliance, the longer the GNA holds out in Tripoli, the more likely that a bastion of Islamist support will remain to threaten regional stability.

The problem with this illiberal secular reasoning is that Egyptians are some of the most overtly devout of all Muslims. They may stop voting for Islamists, but they will not stop reading the Qur’an on the metro or wearing the hijab, much less forsake the religious imperative of creating a Muslim society. They will simply wait for this illiberal secular phase to pass, then mobilize again when the next revolution comes. Because Egyptians will remember the marginalization of Islam, Egyptian leaders are not eager to see this debt come due, so they must sink ever greater resources into controlling thought, without convincing Egyptians to change their Islamist thinking.

This ideological debt is connected with the political and financial debts. If Egyptian leaders acquiesce in the underlying appeal of Islamic politics, then their political patrons in the Gulf will call in their debts and Egypt will not be able to justify its scramble for reconstruction contracts in Libya. If, as seems likely, Egyptian leaders continue to control thought and dissent, Islamist or otherwise, then they have no choice but to see the fight in Libya through to the bitter end, even if it means that Egypt gets substantially less than what it hoped for when it first began supporting Haftar. As in any debtors’ prison, it will not be easy for Egypt to get out.