An official visit to China is like a pilgrimage for German leaders and a ritual for German company bosses.

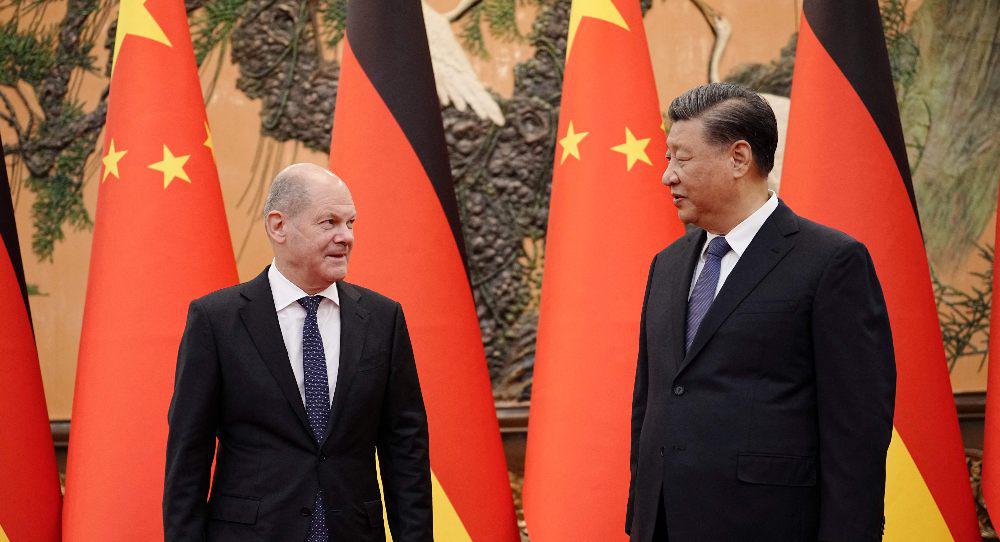

The former Social Democrat chancellor, Gerhard Schröder, went to China six times during his 1998–2005 tenure. His successor, Christian Democrat Angela Merkel, visited the country a dozen times in her sixteen years at the helm. Current Chancellor Olaf Scholz, a Social Democrat, is in China for the second time. In tow, as ever, is a large business delegation. Today Scholz wrap ups his highly choreographed three-day visit with a lengthy meeting with Chinese Communist Party leader Xi Jinping.

The chancellery isn’t looking for any controversy. It keeps a tight grip on the China dossier. Despite attempts by the Green Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock to make German foreign policy more robust, especially by linking it to human rights, the chancellery hasn’t bought into the idea. It subscribes to the EU’s China policy on “de-risking.” In practice, Berlin pursues a bilateral relationship firmly anchored on trade: in 2023, the two countries exchanged €254.1 billion ($269.8 billion) worth of goods, making China Germany’s biggest trading partner followed by the United States and the Netherlands.

Trade aside, more fundamentally, Scholz’s bickering coalition has failed to grasp how it could be a pivotal player that gives Europe the strategic and political depth it lacks. Scholz’s visit to China confirms a persistent reluctance of Europe’s biggest economy to play a central role in the EU, in NATO, and other multilateral organizations.

With the global order no longer stable but rather lurching from crisis to crisis, Europe’s own stability and security is in question. For Germany, its economy depends on stability and predictability. Since neither is a given, Berlin has to change its mindset about making the leap from a reactive, hapless foreign policy to a proactive, strategic one.

Take Ukraine. In his talks with Xi, Scholz urged Beijing to cease sending weapons to Russia and may have even suggested China could mediate to end Russia’s brutal attacks on Ukraine. The second is a non-starter. It hasn’t worked in the past. It is also not clear what Beijing’s aim is in providing Russia with military assistance. China could be hoping to make Moscow even more dependent on Beijing politically, economically, and militarily—and to strengthen the alliance of non-democratic regimes against the West.

But it will not be China that determines the outcome of the war in Ukraine. It will, in large part, be Germany. If Berlin provided the essential military support Kyiv needs, the war’s trajectory could be changed.

For now, Berlin is toeing the U.S. line: don’t provide any lethal weapons to Ukraine; don’t allow NATO to assume the leading role in coordinating military support to Ukraine. The Biden administration wants to control the agenda over Ukraine. It doesn’t want to give Russia any excuse to escalate the war. As it is, President Vladimir Putin is exploiting the instability in the Middle East, Israel’s continuing war in Gaza, and now Iran’s reckless attacks on Israel to escalate his war against Ukraine.

Germany could have played a role in mediating a ceasefire in the Israel-Hamas war. Its past means Berlin’s commitment to Israel’s security is rock-solid. Successive Israeli governments know that and use that when it comes to influencing the EU’s policy toward the Middle East.

But surely Berlin’s special standing with Israel could have given it a special position to mediate? German diplomats duck the question. The ball, they say, is always in Washington’s court. Leaving aside the amount of military aid the United States provides to Israel, that’s not entirely true. Berlin could have used its special relationship with Israel to mediate the conflict with the Palestinians. It squandered that opportunity. Its mealy-mouthed criticism of Israel’s relentless bombing of Gaza and the ensuing deaths and hunger exposes Berlin’s fundamental inconsistencies over basic human rights and international law.

Beijing sees these inconsistencies and double standards. So if Scholz does raise the issue of human rights, censorship and the treatment of the Uyghurs, Beijing can hit back. Europe and the West is in no position to lecture China.

What does this mean for Germany? Reconciling realpolitik—especially economic interests—with values is never easy. But it can be done. It is about speaking out. It is about companies and their shareholders looking at the working conditions of their employees and their subcontractors. It is about Berlin upholding a set of norms it purportedly supports.

It is also about using its economic leverage in a different manner. If Scholz spoke out about what is happening in Tibet, or his concerns about a war between China and Taiwan, or the treatment of the Uyghurs, no doubt Xi would point to the West’s double standards.

But speaking out matters. Even better if it is followed by action. For now, Germany is a reluctant, if not irresponsible bystander. It benefits from trade with China, security from the United States, and a European Union that gives it immense economic influence. Strategic input, to the detriment of its allies, is absent.

.jpg)

.jpg)