Muriel AsseburgSenior fellow in the Africa and Middle East Division at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP)

Over the last decades, a one-state reality with unequal rights has become entrenched in Israel/Palestine. The Israeli-Palestinian antagonism, that had been contained by the Oslo Accords, has relapsed into existential conflict over all of former British Mandate Palestine. The international community has contented itself with crisis management.

Yet, the atrocities committed by Hamas and other militants on October 7, the unprecedented death toll and destruction caused by the war in Gaza, and the high risk of regional and international conflagration all underline that there cannot be lasting stability in the Middle East without an agreement that speaks to the security needs, national aspirations, and human dignity of both Israelis and Palestinians.

This realization should help focus relevant actors’ minds—above all in the United States, Europe, and Arab states—to finally join forces and push first for an arrangement for Gaza and then for a settlement of the Palestine question. Indeed, a separation into two states looks like the only format available as a binational state with equal rights has become even more unlikely than it was before. If international actors can muster enough political will and capital to show the way forward, nudge the parties into a robustly mediated process, and see it through, they could still bring about such an outcome.

Caroline de GruyterEuropean affairs correspondent for NRC Handelsblad

The two-state solution is the only possible road to peace between Israelis and Palestinians. For Israel, living in one state is unacceptable—one day, with current birthrates, Jews could be outnumbered there. This is why Israel invested in the Oslo peace process in the 1990s, which gave snippets of Palestine gradual autonomy. They never got to independence. One reason for this is continued Israel settlement building and military “zoning” in the West Bank. Palestinian villages are scattered all over, cordoned off from each other.

The argument that the settlements are permanent is false. When I lived there from 1994 to1999, many Israelis settled on Palestinian land in the West Bank because it was a kind of subsidized, dirt-cheap suburbia, close to Tel Aviv and the beach. Highways allowed for an easy commute to work or the cinema—it was “just three traffic lights away.” I even met many leftwing settlers, voting for Meretz, who said that if there would be peace one day, they would happily go. The government would buy them out—like it did in the Sinai and later Gaza. One of my articles on them was titled “Hillbillies of the West Bank.”

Of course, many religious and extremist settlers now live there, too. Getting everyone out just requires one thing: political will. It has been sorely lacking so far. And I doubt, alas, we will see it in the near future.

Martin EhlChief analyst at Hospodářské Noviny

Currently, one month after the massacre of Hamas, the two-state solution does not look like a viable option. If the road in this direction was complicated before October 7, right now it looks endless with infinite possible turns into darkness ahead.

However, it is the only long-term option for the whole Middle East. That would require not only goodwill from both sides but also structural changes of the political system—on the Palestinian side, mostly. The viability of such an option would be possible only under the condition of (more or less) democratic rule which is based on the search for compromises.

Yes, Israel has its own troubles related to the personality of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and populism linked to his governance and his coalition. But Israeli society is organized along the principles of democracy and because of that, it can deal with its flaws.

Palestinian society, on the contrary, did not show such a tendency toward democracy and a culture of political compromises. As a result, it is also isolated by its potential Arab allies, not because they would be democrats—which they are mostly not—but because in none of its forms was Palestinian leadership able to formulate and attract attention and support through such a political culture of compromise.

Bruno MaçãesAuthor and foreign correspondent for the New Statesman

I don’t believe a two-state solution is possible anymore, desirable as it would be. About half a million Israeli settlers live in the West Bank. The Palestinian population is being expelled from their homes as we speak and settlers are increasingly running the Israeli government. A two-state solution would always depend on a balance of power between the two sides and Israel now feels so powerful it no longer needs to compromise.

What I witnessed in my last visit to the West Bank a year ago were the heights of despair. Unfortunately, a one-state solution is also impossible. After the brutal attacks from Hamas last month, the scenario of a final expulsion of Palestinians from Gaza and even the West Bank is looming. We may have entered the last throes of the Palestinian national dream.

Marwan MuasherVice president for studies in the Middle East program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace

What are the conditions under which a two-state solution might still be possible in theory?

First, it needs a United States able and willing to lead an initiative not toward another open-ended process that none of the parties believe in anymore, but one where it defines the end game a priori—simply the end of the occupation—and then works backwards in a process to achieve it, all in an election year.

Second, it needs a different Israeli government, not only replacing the current hard-line coalition, but one that is ready to accept a withdrawal along the 1967 border, a significant dismantling of settlements—where the number of settlers today is over 750,000—and to do that all in an atmosphere where the current Israeli public opinion is more hard-line than ever before after the Hamas operation on October 7.

Third, it needs a new Palestinian leadership that emerges through elections across the West Bank, East Jerusalem, and Gaza, which can legitimately sign off on a deal on behalf of Palestinians. Such elections are not of interest to any of the parties.

Are the chances nil? No. Are they anywhere near likely? No. A two-state solution exists only in theory. In practice, it died long ago.

Joel PetersProfessor of government and international affairs at Virginia Tech, United States

With the memory of the Hamas attacks of October 7 still fresh, with the fate of the Israeli hostages unresolved, and with Israel’s military assault on Gaza still ongoing, the idea of the two-state solution seems fanciful today. It will take time for the scars to heal. But at some point, politics and reason will have to replace emotion and anger.

The two-state solution has long been the preferred solution to the conflict. But in reality, Israel and the Palestinians have paid lip service to its implementation.

The two-state solution remains on the table, if only for the lack of any viable alternative. But for it to be realized, it will require a recognition by Israel that it cannot control Palestinian lives with impunity and without cost, and a renewed commitment by the Palestinians to the idea of peaceful coexistence with Israel. It will also demand a far greater commitment by the international community than hitherto shown to hold Israel and the Palestinians accountable for their actions.

Those are big “ifs” and it is far from certain that Israel, the Palestinians, or the international community are up to the challenge. But the past month has shown the human cost of past failures.

Luigi ScazzieriSenior research fellow at the Centre for European Reform

A two-state solution is hard to imagine. The roughly 700,000 settlers in the West Bank, the tilt to the hard right in Israeli politics, and the Palestinians’ lack of a unified leadership pose formidable obstacles.

But the alternatives are even more unrealistic. The illusion that the conflict can be ignored was shattered by the Hamas massacre in October. The total control of the West Bank and Gaza wanted by the Israeli right would make Israel more isolated, less secure, and would stretch its military and financial resources to the limit. And the trust required for a one state in which the two peoples coexist with equal rights is more remote than ever.

The conflict is forcing the United States, the EU, and regional powers to reassess their approach and the assumption that they can safely ignore the conflict. Once the current bout of fighting ends, there could be substantial political changes. Whether Hamas is eradicated or not, many in Israel will think that they have no choice but to empower the Palestinian Authority, since without a functional and self-confident Palestinian entity, there is no alternative to extremism. That would be one first step toward reviving the two-state solution.

Tessa SzyszkowitzCurator at the Bruno Kreisky Forum for International Dialogue, Vienna

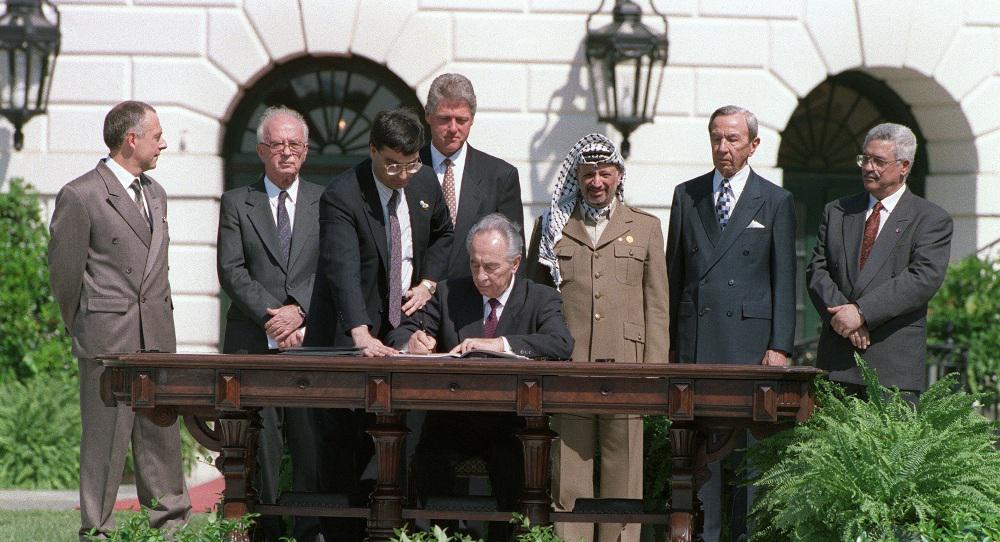

In 1993, leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) Yassir Arafat embraced the two-state solution, as did Israel’s then prime minister Yitzhak Rabin. The Oslo Accords were signed and in 1994 the Nobel peace prize was awarded to Rabin, Arafat, and Shimon Peres, who was the brain behind the historic agreement. The idea—a state each for Israelis and Palestinians—was the first plan that made it seem like a solution for an endless, costly conflict between two peoples claiming the same land could be found by mutual agreement.

But embracing it was not enough. The implemention failed. Thirty years later there is little hope for the two-state solution. A part of the Palestinian society, Hamas in Gaza, is entrenched in violence. Instead of building trust, successive Israeli governments have built more settlements in the occupied West Bank and East Jerusalem. There are around 700,000 Israelis living among 3 million Palestinians on the land earmarked for a Palestinian state. Since the October 7 massacre of up to 1,400 civilians by Hamas in Israeli kibbutzs, violence has taken control of the conflict. Israel is walking into the trap set by Hamas. One month after the attack, there are not many people who believe a peaceful coexistence will ever be possible.

But maybe this catastrophe will eventually lead to new thinking about peace plans. The Austrian Jewish philosopher Martin Buber thought about a binational state in 1946. Palestinian and Israeli thinkers—among them Bashir Bashir, Leila Farsakh, and Avraham Burg—have recently picked these ideas up and considered alternatives to partition. What, they asked, if self-determination for Israelis and Palestinians is not necessarily based on territory but on citizen’s rights? Mediators and peace-seekers must keep their minds open and not give up on a peaceful solution. Because the alternative is endless war.

.jpg)

.jpg)